LIBERATION MIGHT BE PAINFUL

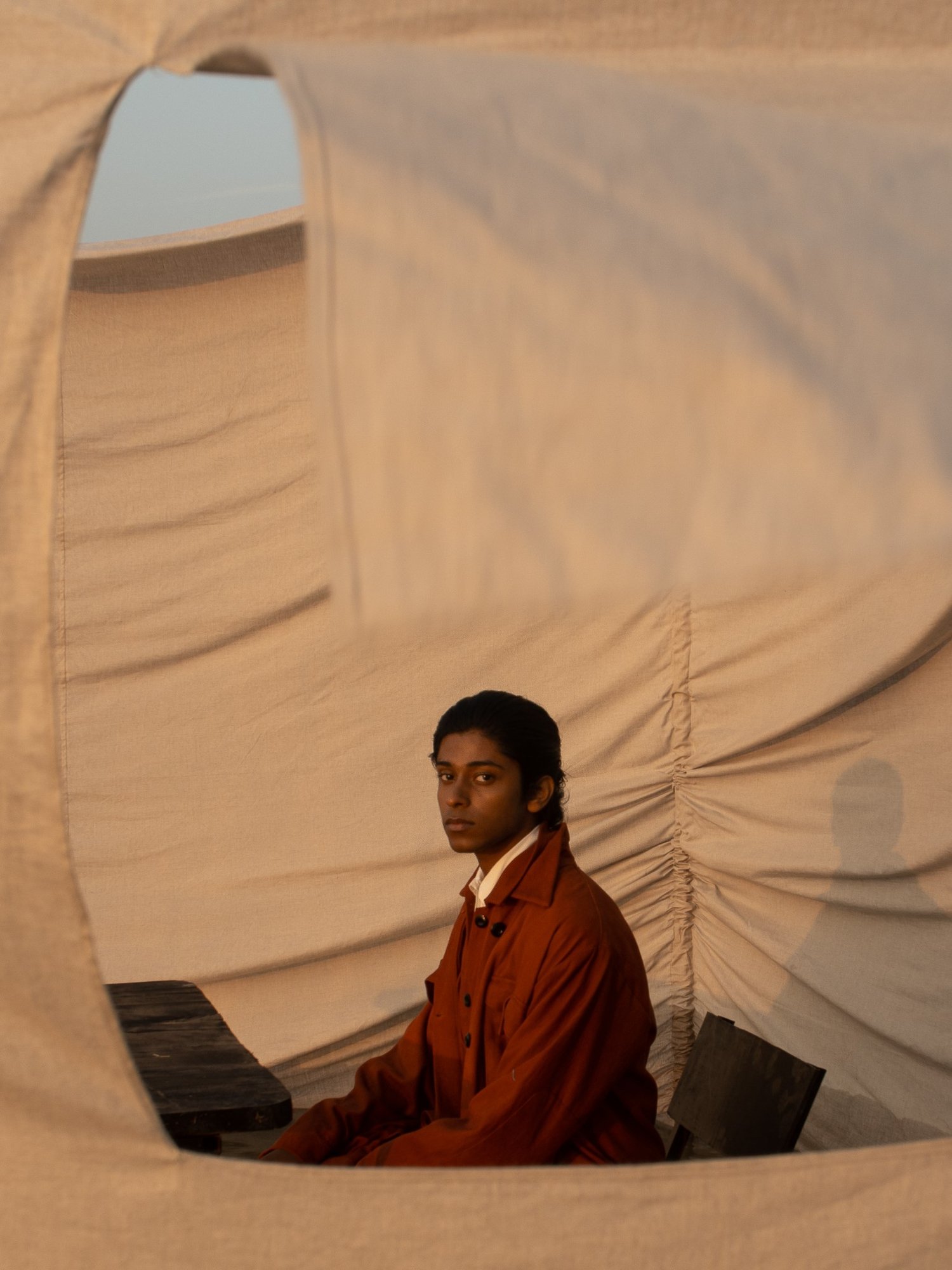

Tanmay Saxena

Hello Tanmay, it is a pleasure to have the chance to learn more about you and your work. First, can you please introduce yourself, telling us a bit of your personal and professional background?

Thank you, firstly let me say that I really enjoyed answering these questions. Felt like time travel and a workout in self reflection, and also revisiting my own work with a little different perspective.

I am Tanmay Saxena, a UK based multi-disciplinary artist and photographer. I was born in India and spent my first 25 years there before I moved to the Uk in 2007. I studied IT and Finance and worked as a Business Analyst for a decade before realising it wasn’t something I liked or was naturally meant to do. Now I feel it was a realisation that took time to come about, but I am thankful that it did. So took the leap of faith and started my clothing label LaneFortyfive. That was my first foray into a creative field and the start of my life as an artist. I feel after that, it was merely about doing what so ever I felt like doing – photography, making films, writing, painting, and doing absolutely nothing at times.

Your photography immediately caught my attention for the poetic yet profoundly human narratives incorporated in your website’s triptychs.

I grew up appreciating poetry in general, how words so easily command the layering and unlayering of emotions, the dressing and undressing of us. And somehow I notice or make that poetry up while looking at and observing people, surfaces, condition of those surfaces, angles, colours.

Growing up in India, you cannot escape people even if you are an introvert like me. But that also lets you be a fly on the wall. When humans seep into the narrative I am capturing, I do not oppose it but let it happen naturally. So sometimes they are completely missing from my images, and at other times, they are either the primary presence or a supporting act.

Can you tell us a bit more about the vision that drives your practice? How did you develop your own way of looking at things and your style?

I grew up on TV and films. As of today, I feel I have learnt more from them than from my life experiences or books. As such, without even trying, when I approach a shoot, in my head I can see a little film built from the images that I am yet to but about to make.

I am a huge fan of childhood and still feel in a number of ways I haven’t grown up and hopfully never will. That surely helps me somewhere to have conversations with inanimate objects and whatever is around me. Like imaginary friends. As such, a solitary chair, surface of water, an electricity pillion, long neck of a horse, or sand in the desert become that character and yearn to tell their story.

We love the series of the caged bird and young man in the sea. What is that about?

‘A liberation’ is a series that to me captures hopelessness, desperation, helplessness, and then hope all over again. The parrot trying to fly free from the cage as every wave brings a possibility of being taken with it. Then there’s the desperation of the man who wants to save the parrot but cannot swim himself as his hands aren’t free. I found myself in such a phase of life where this liberation is extremely slow and painful, seemingly impossible at times. At the time of the shoot, that parrot was 3 years old and lived minutes away from the sea and have not seen the sea ever till that morning. It must have been scary for it to suddenly be in the middle of it, but I’d like to hope it enjoyed a little too.

I personally have a great fascination with masks. Can you tell us about the big white character?

Just the other day I was talking to a very close friend about the movie ‘The Mask’ and how we loved watching it as a kid. This random nobody getting all his dark desires come true simply by being behind a mask. And then there is a line earlier in the film by Dr. Neuman “We all wear masks, metaphorically speaking”.

These kids were making an effigy in the courtyard of a temple. Once done putting it together, they would paint it in the most vibrant colours, the face painted with darkest of black, stuff it all with dry straw and fireworks, and light the demon up on the eve of the festival of Diwali. He is called “Narkasur” – the demon from hell. Now, ever since the BLM movement, I have questioned in my head the concept of white being the colour of peace, calmness, truth, purity in almost all cultures, while black being associated with fear, moral depravity, and evil. Growing up in India gives you the unfortunate experience of seeing this play out in daily life, if one cares to notice. I asked these boys if they can wait and let me take pictures of the demon while he is still white against their own dark skin

You have an interest for the human figure in relation to animals. You portrayed a young girl with an horse and a duck, a man with chicks and a man riding his horse in the desert. There is a tenderness and melancholia in this images that deeply struck us. We would love to know more about them.

I have always been fascinated by how animals and birds look at us. I used to talk a lot to birds and animals as a kid. I still do. I liked how the birds would tilt and move their head with almost every glance they throw at me, each move as if a different line of dialogue. Animals with a snouty head looked at me as if they were judging me, giving me that slant look from one of the sides.

Then I read John Berger’s “About looking”, and the first chapter “Why look at animals” and that inculcated a subconscious habit to capture animals with humans either related to them, or meeting for the first time.

In “Rashida’s girls” I shot Rashida’s 12 year old daughter with one of her ducks and the female donkey. Rashida has 4 daughters, the donkey, a duck, and 2 hens. There is no male member in the household. The inter-species connection between three females in the same frame is something special to me. A sisterhood of sorts. The other two series have animals not known to the humans before the shoot. The little chicken are literally exploring a human body, while the man tenderly helps them when they fall off his chest or head.

The horse and the young man find themselves in a desert, together but also by themselves, on their own. There are moments when the horse and the man look at each other to get a better grasp of the situation they find themselves in, amongst the layers of sands that are there since prehistoric times.

Two series, the pink gloves one and the paper moon one, are more staged than the rest. Are those commercial projects or personal?

The Pink gloves set of images comes from the series “Bodily dreams” where I photographed three differently-abled people and asked them if they see dreams related to their affected body parts. In this case, Monu used to work in a Chemistry lab at a school and lost his hand in an accident there. Since then, in his dreams he has seen his arms being long enough to not have an end, or seeing just hands and hands and hands all around him. We shot the images in the same chemistry lab.

The paper moons on the face was a direct pictorial translation of some poetry I wrote that had a line “He then washes and leaves the moons to dry out during the night” These were both personal projects.

Is there a difference in your practice when dealing with commissioned work rather than your own research?

Commissioned work provides me with a primed canvas in a way that I know the core or the skeleton I am dealing with. How I put the skin and tissues on it is still majorly in my own creative hands. So the process is of a very different nature in commissioned work. When I shoot for myself, there is even a question of what to shoot to begin with. I walk a lot, interacting with what I see, knowing well that an idea can either jump out or calmly enter my subconscious only to show itself in some shape later on.

Speaking of social issues, can we ask you how London and Europe welcomed you? Do you think there is still favoritism based on race in choosing professionals to work with? I’m asking it cause I recently saw a video on instagram of a woman saying she was loosing many her photography pitches against middle-aged white men. I’ve never thought of it before and I think your point of view can be very valuable.

I would have thought otherwise, specially considering the recent spurt in agencies going for a diverse representation of artists. Sometimes personally, it may even feel a little forced or for the sake of it.

The woman you talk about may have had a case where say, 5 out of 5 times she lost out to middle-aged white men, for argument’s sake, lets say because of the meritocracy of the works on offer for evaluation. So for her, it may well seem to be a case of 100% track record and so a narrative starts to form based out of our personal journey, which is a very human thing to happen. But I also feel there is more of a chance of a coloured woman artist getting space over a white middle aged man simply because it will appeal way more to the conscious and woke recievers and is more sellable these days. I am not saying if it is the right way it should happen and that it should replace merit. But that it seems to be the ongoing trend almost.

Personally speaking, I became an artist only when I started creating art in the Uk. I have clearly seen the underappreciation that my art gets in my own native country. The commercial aspect of it is again an altogether different thread.

What are you working on now? What’s next?

I am currently shooting two half-brothers on a holiday having being commissioned by their mother. They are two extremely contrasting personalities and yet being brothers are tied closely. Then there is an old man that lives nearby who can hardly see. He used to be religious, I am told, but stopped when his wife died few years ago. There is a story forming there in my head that I’d like to sit and let brew a little more.

Tanmay Saxena

Tanmay Saxena is a London based multi-disciplinary artist creating through photography, films, fabric, words, and illustrations.

Born in India and living in London for the last 15 years, Tanmay’s work has a duality of two completely different yet complimentary worlds and tones. But the singular thread that runs through it all is of being a story maker. He defines his style as a collusion of fantasy, sometimes with a factual veneer.

Socio-political/emotional commentary from a humanficial perspective, or simply poetry depicted via images rather than words.