VIÉ DE MER

Boris Bincoletto

Words by Boris Bincoletto.

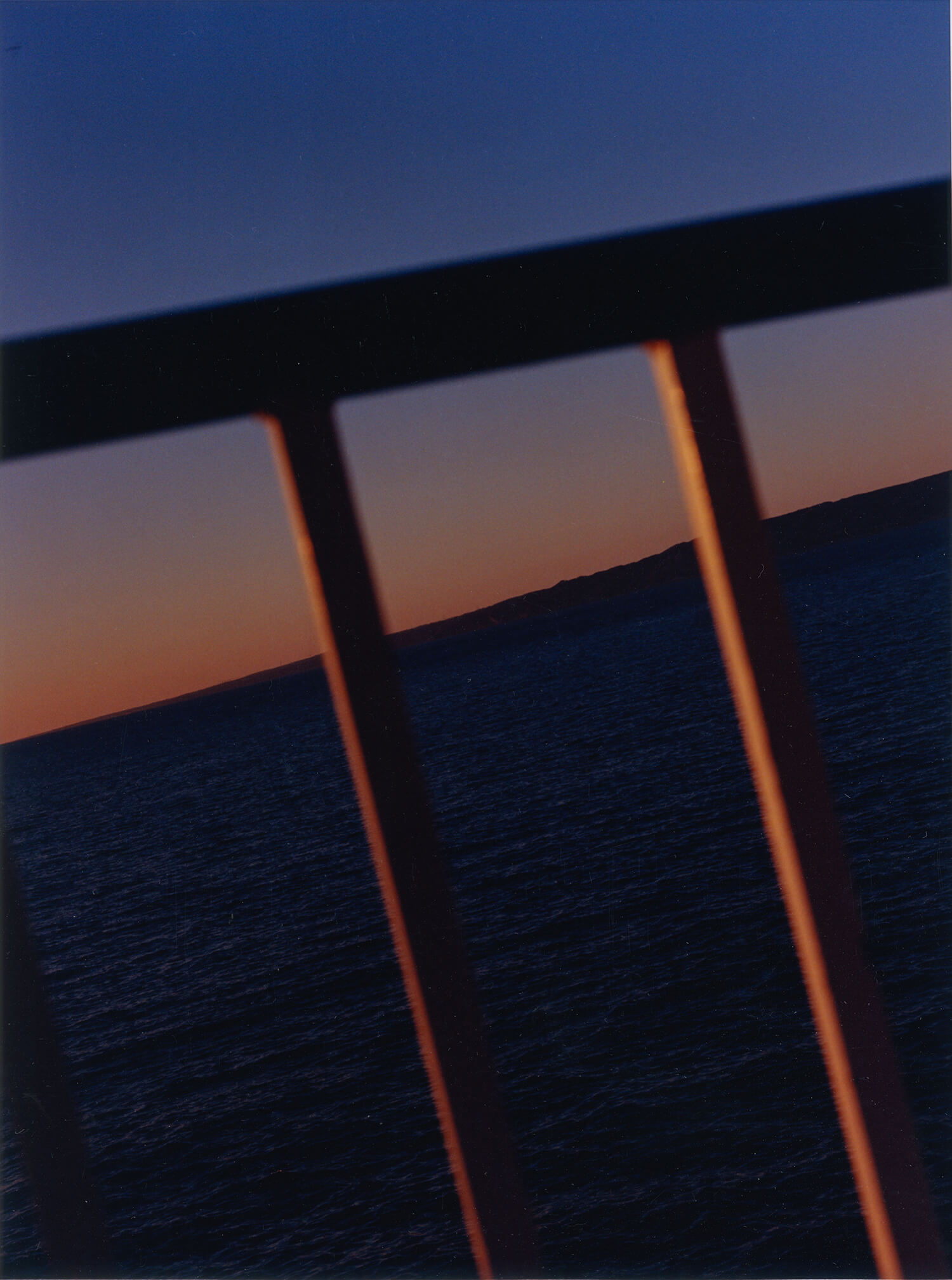

It’s 4:20 AM when we board his little boat. The barquette, as we call it. Typically Marseillaise. It bears the names of his children: Maya – Giorgia. Julien fills the fuel tank a bit. The deck is slippery with the morning dampness. I’m a bit cold, it’s February, but the excitement of this outing at sea takes over. Julien is 40 years old. He acquired this boat in 2020 because he was tired of working in the city. He is one of the youngest fishermen still working in the Marseille harbor and also one of the last to take up this beautiful yet difficult trade. It’s pitch black when we leave the Port of Saumaty, a stone’s throw from L’Estaque. One of the last ports that welcomes fishermen. We navigate for a few minutes guided by his phone’s GPS. He tells me, “look if there’s something shining on the water’s surface.” So I look, but I see nothing. It’s a full night, we could hit one of the breakwaters and I wouldn’t notice a thing. Then suddenly he shouts, “there it is!” Like a beacon in the night, the reflective surface of one of his makeshift buoys indicates the location of the net to be hauled up. He had set it several days ago. A net not very wide but several kilometers long, well-weighted at the bottom to catch rock fish and crustaceans.

Julien gets busy. I’m mesmerized by his calm and energy in such a hostile place. Even though this morning the sea is not very rough. “Sometimes, it’s war.” he tells me with a sly smile.

Proof that danger is part of every outing at sea, but he seems to have accepted and tamed it.

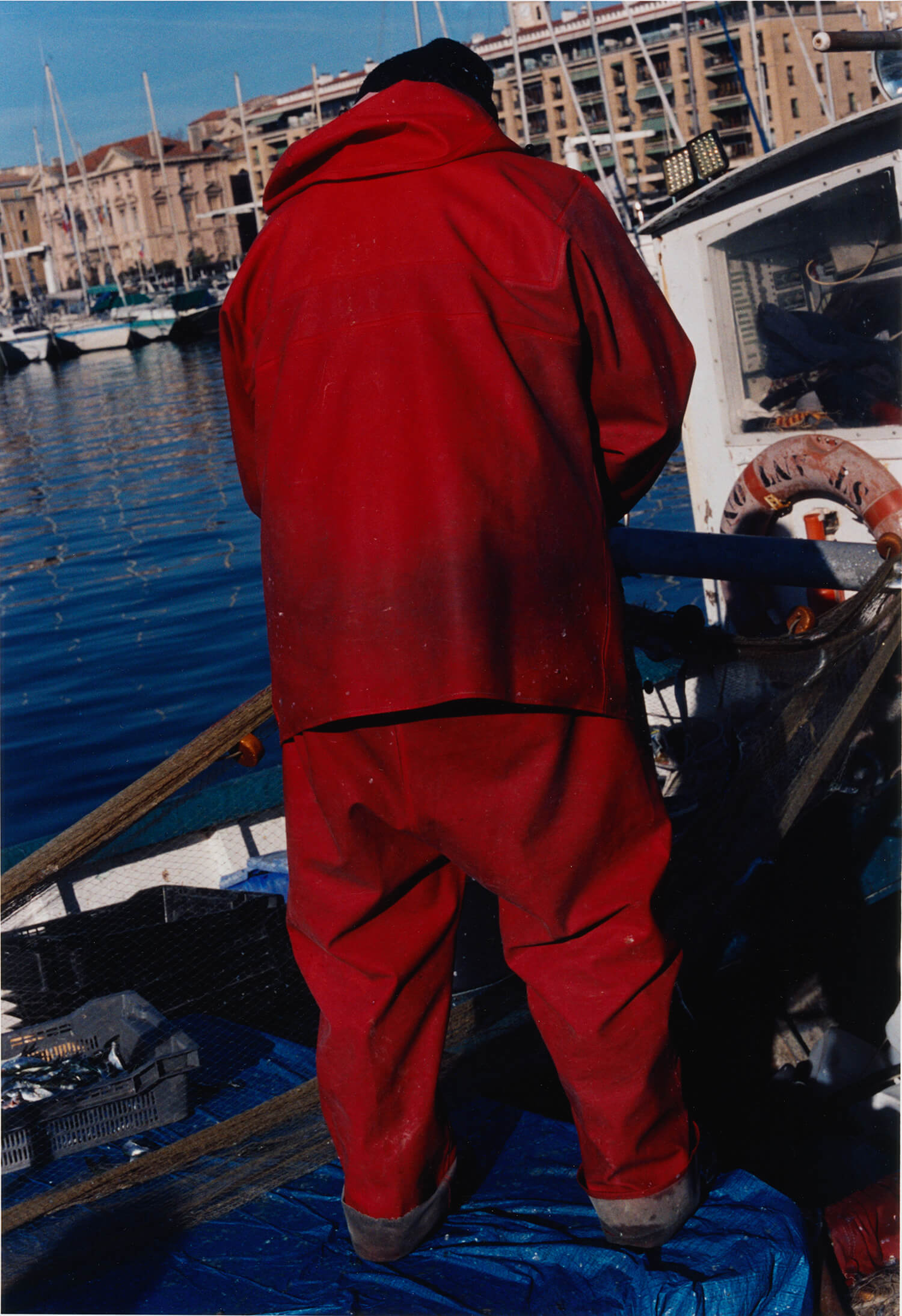

I almost fall into the water every time I bring the camera to my eye. He moves like a tightrope walker on his barquette. It’s dangerous: the fisherman’s trade is the deadliest in France. More than the military. He positions the boat in a precise axis, Julien puts on his gloves, kneels in the hold, and operates the winch motor that slowly raises the net. The operation takes almost an hour. He pulls the net to place it correctly in the hold; it must burn his arms. On his face, a mix of pain and anxiety because this is the moment when he discovers if his outing at sea is profitable or not. I cross my fingers that the net is full of fish.

Instead, stones fall onto the deck, shoes, long pieces of plastic, aerosols, and even what he says is a remnant of a World War II shell. But fish, there are only 4 by the time the net is fully raised.

The realization is shocking. He is clear about it: “Sometimes the sea is generous, sometimes it offers nothing. That’s how it is, it would be too simple otherwise.” He has only been practicing this trade for a few years, so he doesn’t have the same perspective on fish quantities as the older fishermen, but he knows it’s getting worse. That day, via the radio tuned to maritime frequencies, we hear that for the others, it’s famine too. Nothing in the nets.

Then we head back, this time, we navigate longer. Heading towards the Côte Bleue. On the way, we pass by huge cruise ships and even a Supertanker that will end its route at the port of Fos-sur-Mer. It is loaded with thousands of containers. We feel ridiculous next to this floating monster. It is surely loaded with fish caught in the seas of the world and which will also arrive at the Port of Saumaty, but by road this time.

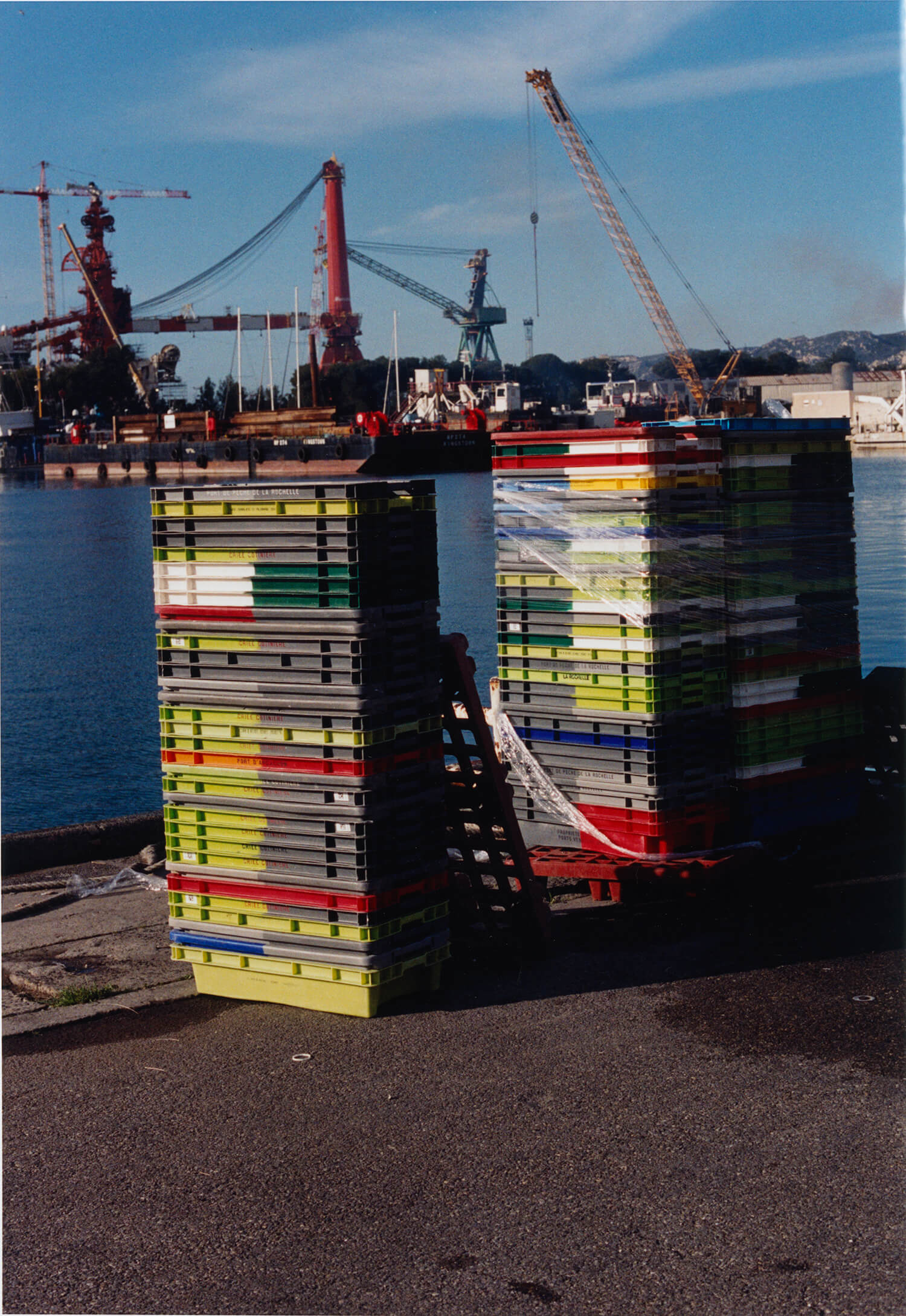

At the fishing port of Marseille, more fish arrive by road, by truck, than they do by sea. It’s crazy.

Once at the port, hundreds of people prepare it to flood the local market. With fish that is therefore not local. This reality makes Julien’s work so ephemeral and artisanal compared to the enormity of the global fish trade. It’s David against Goliath.

Julien tells me about the administrative burden he faces. Almost every return to the port, a maritime affairs officer is there to monitor, note, check what these last artisanal fishermen bring back. A bit like farmers who, in addition to practicing a hard job, have to deal with an administration that complicates everything. A fisherman like Julien catches between 3 and 6 tons of fish a year. The Annelies Ilena, the largest fishing vessel in the world, currently operated by the Saint-Malo Fishing Company, catches 400 tons of fish per day. To partly make surimi. And that, with almost no control from the competent authorities and by shamelessly scraping the seabed. It leaves me speechless. Yet Julien continues to explain. He tells me everything about his trade and ends up confiding that he couldn’t meet his needs and those of his family solely with his fishing and that he has to do odd jobs on construction sites in the afternoons.

That day, we returned to the port at 11 AM, and all I want is to go home, shower, and sleep but for Julien the day is not over. He has to deliver his fish to his reseller, prepare the boat for the next day, and then family life takes over. But then what drives you to continue? To get up every day at 3 in the morning, to go to sea, and sometimes risk your life? “At least, nobody bothers me when I’m at sea, and then look around you, isn’t it wonderful to work here?” He’s right about that, nautical twilight has just passed, the light is amazing, you can see Marseille on one side, the calanques of the Côte Bleue on the other. Yes, it’s breathtaking. But that’s not the only reason you keep going, is it? “No, actually I’m proud of this job, proud to perpetuate a history and folklore that is disappearing, proud to sail with a boat designed 300 years ago. Happy to know that my daughters are proud of their fisherman father. It’s a whole that drives me to continue. I could be rational, take a calculator and add up what I leave to the sea compared to what it gives me, but I don’t want to, I’m not a rational person so I continue.”

Boris Bincoletto

Boris Bincoletto is an Italian-French photographer and director. He discovered photography through documentary films and particular attention to light when working primarily in film and printing his photographs at the enlarger. He works with magazines and for designers creating gentle floods of light.

His personal work focuses on the effects of time on our surroundings and attempts to highlight characters we forget or see little.

He is about to publish his second photography book published by Éditions Révolues. A photographic and textual story about his personal reconstruction on an imaginary island in the Mediterranean.